In 1944, Bette Davis was determined to take charge of her career. Her studio, Warner Bros., took advantage of this position. They contracted with Davis to do five films in which she would star, and also produce. This actually worked to Warner’s advantage, since the studio made Davis and other stars “producers” in name only, allowing them to receive more favorable tax treatment, which actors desired, without having to give them raises in salary.

So, serving as producer, Davis believed she could obtain control over her pictures, and also secure a tax break. In fact, Davis made only only one of the five films she contracted to “produce, and the director, the German national Kurt Bernhardt, wound up disputing the one picture she was credited with producing: “Despite what she claims in her autobiography,” he claimed, “she did not produce A Stolen Life, although it was made by her production company. I will face her any day on that. It had, in fact, no official producer.” Davis responded to this charge, “We were producers, Kurt and me.”

The production company was called B.D., Inc. Davis called her daughter B.D.

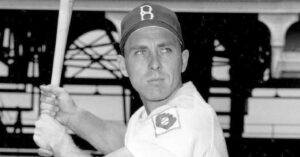

Bernhardt cast Glenn Ford, just as he got out of the Marine Corps. But Davis needed to approve him. “It worried her for a while that she might look too old for him,” said Bernhardt. Davis was then 37, Ford was 29.

Shooting ran from mid-February, 1945, through mid-July. It took until May 1 of the following year to stage the New York opening. The domestic release date was July 6, 1946. The reason given was that Warners used the film to highlight the twentieth anniversary of sound in motion pictures. No one could understand why, however.

The film, a far fetched soaper, received mixed reviews. Bosley Crowther for The New York Times wrote: “A distressingly empty piece of show-off.” The notice in CUE: “A series of glib, overworked dramatic clichés. A ‘true confessions’ tearjerker.”

Of course there was never any keeping Bette Davis down, who fought back stating, “The public liked it, and the popular heart is more true a judge of a picture than any army of critics!”

Walter Brennan said of Davis, “I’m not surprised her marriages never lasted. She was too much woman, hellcat-variety, for any man to keep up with. I think she just wore them out. I’m convinced she enjoyed all the chaos and that she went out of her way to generate it!”

Bette Davis played twins here, and then once again in the murderous melodrama Dead Ringer (1964).

For the year 1947, in triumph, as usual, Bette Davis earned more money than any other female in the United States.

Ford won the key role in Gilda from his performance in A Stolen Life. Davis told him to smoke a pipe in the film, he remembered. “That will make you look older,” she explained.

“I last saw her flying from from London to Los Angeles a couple months ago.” Ford said of Davis in 1989. “She told the flight attendant, ‘Tell Mr. Ford to come sit with me.’ It wasn’t, ‘Would he come and sit with me?’ No, it was an order, so I obeyed, and I’m glad I did. I had made A Stolen Life with her, and from that came Gilda. So she was responsible for everything good that happened to me.”

Variety’s reviews always meant the most, and for A Stolen Life, their critic said, “Bette Davis is a triple threat proposition. In addition to playing the dual role, the actress makes her producer debut. It’s a femme story of heartache. Opulent production values, marquee strength of Miss Davis’ name, and appealing story will have femme audiences add up to hefty returns. Since it’s a woman’s story, dialogue hands plenty of clichés to male players, particularly Ford. Photography is the best yet.”

P & L: the final negative cost came in at $2,217,000. The worldwide gross was $4,785,000 to yield a quite satisfactory net profit of $1,614,000. That is a return on investment of 73%!