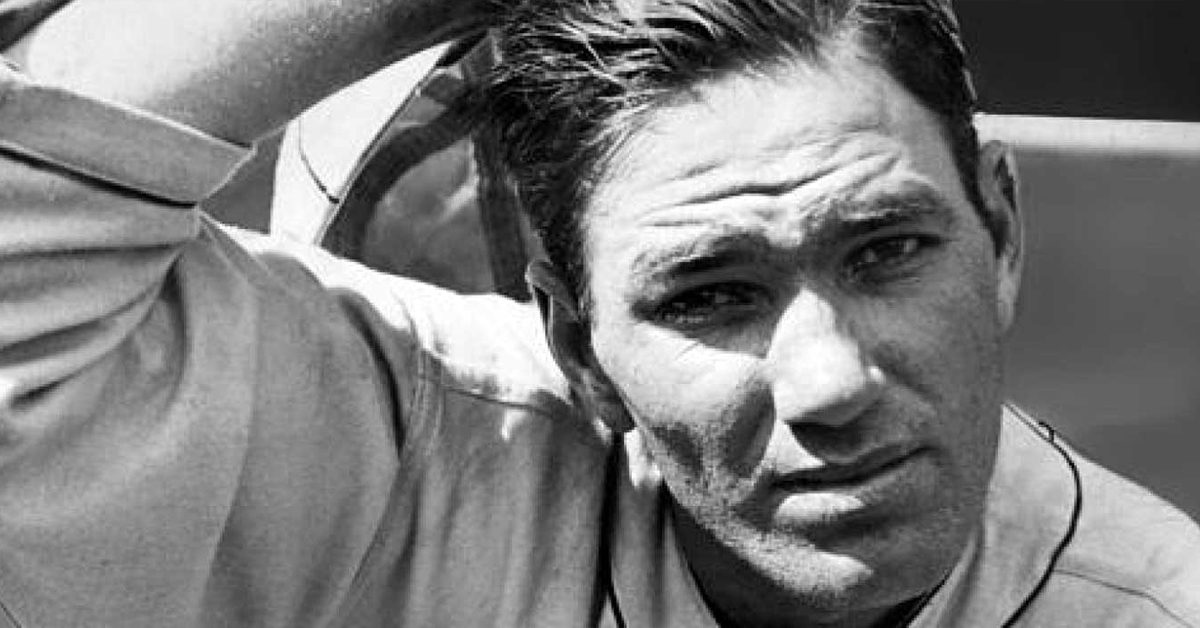

Hall of Fame “Gas House Gang” star pitcher Jerome Herman Jay Hannah “Dizzy” Dean often belied his folksy “good ol’ boy” personality, the character who laughed a lot, did crazy things, and mangled the English language. He was actually pretty shrewd, and died a wealthy man. He invested wisely in oil and Texas real estate.

And early on he knew the value of intellectual property rights and celebrity endorsements. After the 1934 World Series he got paid for writing about it through the Christy Walsh Syndicate; for breakfast cereal endorsements; for a harmonica endorsement; for an appearance at the famous Roxy Theater in New York; for an appearance in a movie short subject; for a radio appearance with Al Jolson; for use of his name on hats; for another radio appearance with Kate Smith; for making a series of radio transcriptions; for the use of his name on children’s writing tablets in schools; for a barnstorming tour across America where he pitched against the equally renowned Satchel Paige (“the black Dizzy Dean”) and a Negro League team in a time before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier — and Dizzy Dean was just getting started.

So during the Depression when most Americans were mired in joblessness and hopelessness, Dizzy Dean was cleaning up. “Doggone but I’m gettin’ tired of havin’ to take in all this money,” he complained. “I never knew dough could be so much trouble. It’s ‘Diz, please take a thousand for endorsin’ watches. And please, Diz, take this check for baseball caps.’ And now I’m liable to have to go into the toothpaste and shavin’ cream business. Doggone, I’m gettin’ tired of it all. For two cents I’d jump the club and go fishin’ up to Novus Scofus.”

Dizzy Dean’s personality was electric and his baseball prowess was unmatched. “It ain’t braggin’ if you can do it,” he used to boast. And he could do it all right! Fans loved the way Dean was always mouthing off to the press, too. What a character.

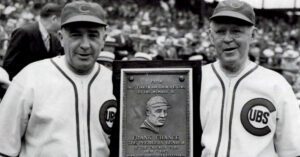

Of course he played for the St. Louis Cardinals. This was a time in baseball when St. Louis had the Cardinals in the National League and the Browns in the American League; when Chicago had the Cubs in the National League and the White Sox in the American League; when Boston had the Braves in the National League and the Red Sox in the American League; when Philadelphia had the Phillies in the National League and the A’s in the American League; and when New York had the Giants in the National League and the Yankees in the American League.

The zenith for Dean and the Gashouse Gang was 1934. Three years later he sustained an injury that caused him to alter his delivery. The different pitching motion resulted in a sore arm. He never fully recovered.

In 1941 Dizzy Dean signed on as the radio play-by-play broadcaster on games for both St. Louis teams, the Cardinals and the Browns. Dean was on his way to eventually becoming the colorful announcer beloved across America on CBS Television’s Major League Baseball GAME OF THE WEEK during the 1950’s and 1960’s. Prissy English teachers in schools were horrified that Dean was so celebrated, but every baseball-playing kid in the country loved him for saying things like “he slud” instead of slid..

While still offering commentary only locally for the two St. Louis teams in 1947, Dean pulled another of his classic stunts. During World War II, when most of the top stars in the game were fighting overseas, the lowly St. Louis Browns somehow snuck in and won their only American League pennant (this franchise has long since been uprooted and re-emerged as today’s Baltimore Orioles). By 1947 the Browns had reverted to form and lost 95 games and were back on the bottom, last in the American League behind even the lowly Washington Senators.

Poor Dizzy Dean got awfully frustrated watching the Browns lose games, especially frustrated watching their woeful pitching staff. During one game, Dean moaned and said, “Don’t walk that guy! Doggone it, brother, I swear I could do better than a lot of these guys.”

Since the Browns were so bad, attendance was generally low. It was near the end of the season when the White Sox came to town. They were out of contention, so this series meant nothing. Yet on this particular day, the stands were packed. A sellout crowd had assembled. It was 1947, the year Jackie Robinson changed the game, that was the big story all season — until now! It had been six years since he’d thrown a baseball, but Dizzy Dean was given a St. Louis Browns uniform and sent to the mound that day! He would be their starting pitcher! Could he back up his frequent complaints about the Browns’ staff — that he could do better? That the old man sitting up in the stands could come down and out-perform the kids he criticized all the time?

Fans who listened to Browns games on the radio had heard ol’ Diz roast the Browns pitchers and wrote letters to club management pleading for them to give Dizzy Dean the ball — to let him pitch, to see what the “old man” could do, if anything.

As he said so often, “it ain’t braggin’ if you can do it.” And he did it, once again. That day Dizzy Dean took the mound and threw four shutout innings, giving up three meaningless hits, and to top it off, during his only at bat he smacked a double! It had been a while since Dean had done any running and he pulled a muscle rounding first base. They had to remove him from the game. His wife was screaming at the Browns manager to get her husband out of there before he really hurt himself!

It was the last game this national folk hero would ever pitch in the big leagues.

How about that?