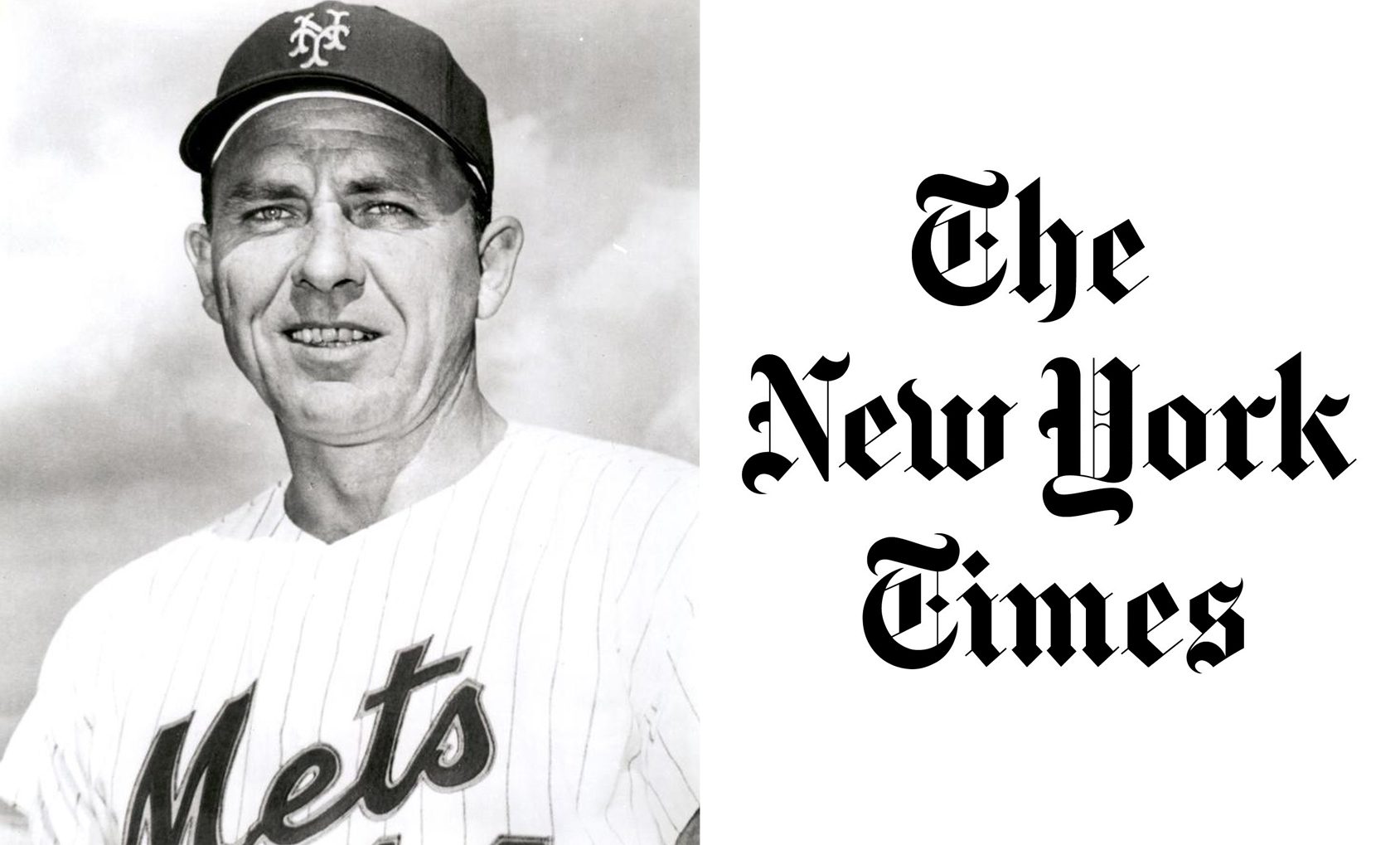

Gil Hodges struggled to make the Hall of Fame because voters had to consider him as a player or as a manager. Hodges was decidedly both and is finally headed to Cooperstown.

They were sons of the 1920s, Indiana teenagers when Brooklyn came calling. Gil Hodges, from Petersburg, was about three years older than Carl Erskine, from Anderson. One day, in 1950, they shared an afternoon for the ages: four home runs for Hodges and a complete game — with four hits at the plate — for Erskine. The pitcher was friendly with the slugger and his family.

“I knew his brother and I knew his father,” Erskine said by phone from Indiana on Monday. “All three of those men died of the same heart condition. It was rare, but one of the biggest, strongest men on the team was Hodges, and yet his heart was not strong and it took him too early in life.”

Hodges was just 47 when he died on Easter in 1972, in West Palm Beach, Fla., after a round of golf with his Mets coaches during spring training. Erskine turns 95 on Dec. 13, one of just two living Dodgers — with Roger Craig — who played for the winners of the 1955 World Series. Their candle is flickering, but their legend burns brighter now. Hodges is a Hall of Fame player.

He made it on Sunday when a 16-person panel, at last, delivered a different verdict than all the others. Denied for 15 years by the writers, and again by several iterations of the veterans committee, Hodges will finally have a plaque in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“It’s a great, great thing that happened for our family,” Gil Hodges Jr. said on Monday. “We’re all thrilled that Mom got to see it, being 95. This was perfect timing.”

Joan Hodges, Gil’s widow, rode with him up Broadway in an open convertible in October 1969, ticker tape swirling like snowfall. That World Series triumph, as the manager of the Miracle Mets, was one of three for Hodges. He also helped the Los Angeles Dodgers win a championship in 1959, his last big year as a player.

Hodges averaged 30 home runs and 101 runs batted in per season from 1949 through ’59. He hit 370 homers overall, and in May 1963, when Hodges retired, only two right-handed hitters (Jimmie Foxx and Willie Mays) had more home runs. Now there are more than 40 right-handers ahead of Hodges.

His fielding also set him apart. Gold Gloves were first presented in 1957 — the Dodgers’ last year in Brooklyn and Hodges’ 10th full season — and Hodges claimed the first three. He did not win on name recognition, either.

“A lot of first basemen are good with the glove; Ted Kluszewski, for instance, was an outstanding first baseman, but compared to Hodges he didn’t have the range,” Erskine said. “Gil could go broadly afield. He’d been a catcher at one time earlier, and so he was accustomed to fielding bunts out in front of home plate. He’d charge on a bunt, field the bunt, turn and have a catcher’s throw to second base and nail the runner. I never saw another first baseman who would even try that. But he was agile and he had great hands.”

Hodges may have had the most massive hands in baseball. That is what Roger Kahn wrote in “The Boys of Summer,” at least, confirming it with this quip from shortstop Pee Wee Reese: “Gil wears a glove at first base because it’s fashionable. With those hands, he doesn’t really need one.”

Hodges’ case for Cooperstown had long been perplexing. He was gaining momentum on the writers’ ballot before he died, then spent more than a decade in a holding pattern, with 49 to 63 percent of the votes. Historically, nearly every candidate to get that much support eventually gets in, but the committees had never nudged Hodges across the 75 percent threshold.

The 1993 vote was especially cruel. Roy Campanella, Hodges’ wheelchair-bound Brooklyn teammate who would die that summer, could not attend the meeting in person and was not allowed to vote by phone. The family was crushed, at least in the moment.

“That hurt a little different, because we had the 12th vote,” Gil Jr. said. “But you know what? When the day ended, everything was still the same. We just went and moved forward.”

One problem for Hodges was that candidates are supposed to be judged on a playing or a managing career, not both. By strict interpretation, then, Hodges’ 1969 title with the Mets could not have pushed him over the borderline. But that achievement is integral to his story, and his players have long credited Hodges for skillfully using role players and insisting on a clean style of play.

After the Mets beat Atlanta in the 1969 National League Championship Series, outfielder Cleon Jones recalled a couple of years ago, the Braves’ Hank Aaron warned a Baltimore scout that the favored Orioles might be in trouble.

“If you don’t play the best baseball that you’ve played all year, you’re going to get beat,” Jones said, recalling Aaron’s message. “This is a good team, they don’t make mistakes and they do all the things that it takes to win.”

Jones continued: “And I attribute that to Gil Hodges. Had it been anybody else — Yogi Berra or Wes Westrum or even Casey Stengel as the manager, you wouldn’t be talking about the ’69 Mets. We won because of our leader, which was Gil Hodges, because he instilled that kind of attitude in the ballclub and he didn’t allow us to make mistakes.”

Hodges’ Brooklyn teammates did not expect him to manage, Erskine said, because he was so composed, never prone to tantrums — the opposite, in other words, of the Orioles’ Earl Weaver. A manager without a “forceful personality,” as Erskine put it, was somewhat rare.

“But if you talk to somebody that played for him as a manager, like Tom Seaver with the Mets, he said, ‘Hodges was quiet, but he had a look that could burn your shorts off,’” Erskine said. “So if he gave you this look, he didn’t have to say anything. He was not a holler guy, but he gave you the look and you had the meaning of it already.”

The Mets could not build on their championship under Hodges. They finished 83-79 in each of the next two seasons, placing third both times. Ed Kranepool, their first baseman, insisted Monday that the Mets would have won “many, many more pennants” had Hodges lived. But of course there is no way to know.

It is a safe bet, though, that Hodges would have accepted his Hall of Fame election with understated grace, not wanting much of a fuss. He built a legacy and raised a family in New York, but he was Indiana, through and through.

“Down-to-earth people — that was his background, the way he was raised,” Erskine said. “Humility was a part of his life. It came just as natural as breathing. So that was kind of his trademark, and it was a good one.”